By: Rob Mulder

For: www.europeanairlines.no

In 1923 Roald Amundsen attempted to fly from Wainwright, Alaska (USA) across the North Pole to the islands of Spitsbergen. Amundsen’s friend Consul Haakon Hammar and Junkers propaganda director Friedrich Andreas Fischer von Poturzyn organised a relief party to help in case Amundsen’s aircraft would not complete the flight. But Roald Amundsen had to cancel the flight due to problems with the Junkers JL-6.

Roald Amundsens failed polar flight

In the USA the Junkers Larsen JL-6 had proven itself on numerous long distance flights, among them one in October 1920 from New York to Los Angeles. In May 1921 a Junkers Larsen JL-6 with the American pilot Stinson at the controls made an endurance flight and stayed 26 hours and 19 minutes in the air. Therefore Roald Amundsen believed this aircraft would be ideal for his flights. He also believed that the duralumin would be ideal for Arctic and Antarctic conditions. The aircraft for Roald Amundsen was delivered in May 1922 in New York and the Norwegian pilot Oscar Omdal was asked to fly the aircraft. In order to get to know the aircraft Omdal flew the aircraft from New York to Seattle, i.e. from the east coast to the west coast. While flying above the oil fields of Pennsylvania (near the city of Marion) the engine stalled and the subsequent forced landing led to the total destruction of the aircraft. Immediately another Junkers Larsen JL-6 was purchased, but this time the aircraft was delivered in boxes to Seattle, where “Maud” had moored. The Junkers Larsen JL-6 and the Curtiss Oriole were taken on board and the ship departed in northern direction. Oscar Omdal and Roald Amundsen went ashore in Wainwright at Alaska’s northern coast. The Junkers-Larsen JL-6 was unloaded as well. The idea was to make a long distance flight in northern direction and try to come as far as possible. The new Junkers Larsen JL-6 was now named “Elisabeth” (as the Curtiss Oriole named after Kristine Elisabeth Bennet) and the cases with the aircraft were stored on land. But the summer and autumn of 1922 was marked with strong winds and storms making it impossible for the two to take off. They had to build a house and stay there during the winter. The next spring a new attempt would be made and the date 20 June 1923 was set.

In the USA the Junkers Larsen JL-6 had proven itself on numerous long distance flights, among them one in October 1920 from New York to Los Angeles. In May 1921 a Junkers Larsen JL-6 with the American pilot Stinson at the controls made an endurance flight and stayed 26 hours and 19 minutes in the air. Therefore Roald Amundsen believed this aircraft would be ideal for his flights. He also believed that the duralumin would be ideal for Arctic and Antarctic conditions. The aircraft for Roald Amundsen was delivered in May 1922 in New York and the Norwegian pilot Oscar Omdal was asked to fly the aircraft. In order to get to know the aircraft Omdal flew the aircraft from New York to Seattle, i.e. from the east coast to the west coast. While flying above the oil fields of Pennsylvania (near the city of Marion) the engine stalled and the subsequent forced landing led to the total destruction of the aircraft. Immediately another Junkers Larsen JL-6 was purchased, but this time the aircraft was delivered in boxes to Seattle, where “Maud” had moored. The Junkers Larsen JL-6 and the Curtiss Oriole were taken on board and the ship departed in northern direction. Oscar Omdal and Roald Amundsen went ashore in Wainwright at Alaska’s northern coast. The Junkers-Larsen JL-6 was unloaded as well. The idea was to make a long distance flight in northern direction and try to come as far as possible. The new Junkers Larsen JL-6 was now named “Elisabeth” (as the Curtiss Oriole named after Kristine Elisabeth Bennet) and the cases with the aircraft were stored on land. But the summer and autumn of 1922 was marked with strong winds and storms making it impossible for the two to take off. They had to build a house and stay there during the winter. The next spring a new attempt would be made and the date 20 June 1923 was set.

By May 1923 the aircraft was assembled again and ready for the first flight. On 11 May 1923 the first test flight was made. Amundsen wrote in his diary: “He approached the houses, losing altitude very quickly, and barely missing them. He ended up down on the lagoon, a few metres from where he had taken off. The left ski cut across under the engine, flipped a half circle and overturned on the right wing. Oskar Omdal was never in any danger. We all ran over to the aircraft. The landing gear that was fastened to the left ski was broken. Omdal said that the engine had been working very unsatisfactorily … after this, I have little hope of a flight.” They tried to do some repairs, but by 10 June it was clear that they had to give up and cancel the entire flight.

Jfa informed that the Junkers Larsen JL-6 had been an old aircraft and that the engine (a 185 hp BMW III) had not been reliable. The Consul Haakon Hammer (the one that took care of the financial side of the expedition) offered on behalf of Junkers Flugzeugwerk AG – Jfa a new aircraft that Amundsen could use for a flight from Spitsbergen towards the North Pole and back. But Roald Amundsen was fed up with the problems with the Junkers-aircraft and declined the offer.

The relief party is set up

The Norwegian government was aware of the danger of the expedition and wanted to set up a relief party. In case of problems the Hansa Brandenburg aircraft of the Navy would fly towards Amundsen and Omdal and pick them up at the edge of the North Pole ice. Jfa (already in a dispute with John M Larsen, who had sold the obsolete aircraft to Roald Amundsen) took responsibility and offered the Norwegians a Junkers Type Fw (1). The aircraft was to fly to Kristiania (now Oslo) to join the Norwegian relief party that would sail with the MS “Flint” from Horten to Spitsbergen. This Junkers Type Fw was registered in Germany as D192 (WNr 616) and named “Meise”. The two years old aircraft unfortunately crashed on 10 June near København (Copenhagen, Denmark) and had to return to Germany for repairs. The Norwegian relief party could not wait for the replacing aircraft and decided to leave Horten.

Amundsen’s friend Consul Haakon Hammar and Junkers’ propaganda director Friedrich Andreas Fischer von Poturzyn decided to put up their own relief party and sail to Spitsbergen. On 23 May 1923, the Junkers Type Fw D260 “Biene” (WNr 650) had made its first flight and was transferred via Amsterdam (Schellingwoude air field, see enclosed picture) to Hamburg. It was in the beginning of June lifted on board the Norwegian steamer “Merkur” for transportation to Bergen. After a stormy three days voyages across the North Sea it arrived on 12 June at the Norwegian fjord city Bergen. It was lifted ashore and used for some joy ride flights around Bergen with local notabilities.

Amundsen’s friend Consul Haakon Hammar and Junkers’ propaganda director Friedrich Andreas Fischer von Poturzyn decided to put up their own relief party and sail to Spitsbergen. On 23 May 1923, the Junkers Type Fw D260 “Biene” (WNr 650) had made its first flight and was transferred via Amsterdam (Schellingwoude air field, see enclosed picture) to Hamburg. It was in the beginning of June lifted on board the Norwegian steamer “Merkur” for transportation to Bergen. After a stormy three days voyages across the North Sea it arrived on 12 June at the Norwegian fjord city Bergen. It was lifted ashore and used for some joy ride flights around Bergen with local notabilities.

On 12 June the seaplane, now renamed as “Eisvogel” (Kingfisher), was hoisted on board the Norwegian steamer “Eidshorn” that would bring it to Tromsø in the far north of Norway. Here it arrived on 21 June, where it again was lifted ashore and used for some joy ride flights. During the sailing up north, the relief party was informed that Roald Amundsen and Oskar Omdal had abandoned their attempt to cross the North Pole. Nevertheless, the relief party decided to continue to Spitsbergen and turn the relief party into an expedition. On 1 July they departed the harbour of Tromsø on board the Dutch coal steamer “Ameland” (2). After two days the vessel arrived at Green Harbour on Spitsbergen and again the aircraft was lifted on the water. On 4 July the whole expedition was transferred from Green Harbour to a nearby Radio and Whale station, where a camp was set up. The party present on Spitsbergen consisted out of the pilots Arthur Neumann and W Löwe (leader of the expedition), the mechanic Holbein, the Swiss pilot and photographer Walter Mittelholzer, the Danish Junkers-pilot Fredy Duus (who acted as interpreter) and Consul Haakon Hammer.

Flights above Spitsbergen

The next day the seaplane took off for a test flight above the Advent Fjord, a flight that went smoothly. But on 6 July the Junkers Type Fw, D260 Eisvogel departed for the first long distance flight. It was a 300km long flight over the Is Fjord and the Dickson Bay. During this flight pictures were made for later study. This flight was followed by a 400km long flight in northern direction to the Ekmann Fjord, Tre Kronor mountains, the island Prins Karl Forlandet and the Forland Sound. But the most impressive flight was made on 8 July 1923 with the “Eisvogel”. On that day it made a 1,000km long flight around the largest island of Spitsbergen, the island Vest-Spitsbergen. Below will follow a closer look to this part of the expedition.

Meanwhile after the return of the Junkers Type Fw, D260 “Eisvogel” to Cape Linne (the radio and whale station) the seaplane made numerous short joy ride and photographic flights above Spitsbergen. In the middle of July the aircraft was hoisted onboard the coal steamer “Ameland” again for transportation back to the Netherlands. After one week sailing the crew and aircraft arrived in the harbour of Rotterdam. Consul Haakon Hammer had already disembarked during the stop in Bergen. The seaplane was taken off the steer of the ship. On 24 July at 10 am it arrived at Waalhaven, the airfield of Rotterdam. The seaplane was transferred to Germany and later operated by the Estonian airline company A-S Aeronaut, where it was registered as E15. In March 1929 it was sold to Deruluft (registered as RR40). And … in the end it ended its life in Norway as N-44/LN-ABH.

Meanwhile after the return of the Junkers Type Fw, D260 “Eisvogel” to Cape Linne (the radio and whale station) the seaplane made numerous short joy ride and photographic flights above Spitsbergen. In the middle of July the aircraft was hoisted onboard the coal steamer “Ameland” again for transportation back to the Netherlands. After one week sailing the crew and aircraft arrived in the harbour of Rotterdam. Consul Haakon Hammer had already disembarked during the stop in Bergen. The seaplane was taken off the steer of the ship. On 24 July at 10 am it arrived at Waalhaven, the airfield of Rotterdam. The seaplane was transferred to Germany and later operated by the Estonian airline company A-S Aeronaut, where it was registered as E15. In March 1929 it was sold to Deruluft (registered as RR40). And … in the end it ended its life in Norway as N-44/LN-ABH.

Upon his return in Bergen and Copenhagen, the Consul Haakon Hammer said he had offered Roald Amundsen to make the flight with a new Junkers Type Fw to the North Pole from Spitsbergen in stead from Alaska. He said that he had sent a telegram to Roald Amundsen, but was not sure if this ever arrived. A reply was never send.

1,000km flight to the pack ice (3)

The following extract comes from the account as published by Junkers in 1923. It is likely to have been written by the leader of the expedition, the Junkers-pilot W Löwe. Walter Mittelholzer, who published it in book form, has written the official account and had the rights. He published in 1923 the book: “Im Flugzeug dem Nordpol entgegen. Junkers’sche Hilfsexpedition für Amundsen nach Spitsbergen 1923“.

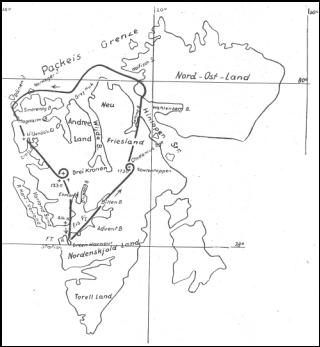

At Saturday, 7 July the weather at Spitsbergen cleared considerably. In this part of the world predicting the weather is not an easy thing. Mountains were still covered by a thick pack of snow and cold winds came from the north. But during the night from 7 to 8 July 1923 the German pilot W Löwe sat on his bench overlooking the Is Fjord and enjoying this beautiful midsummer night. The 1,000 km flight had already been planned and W Löwe was thinking about the routing while sitting on his bench. The plan was to fly from the Is Fjord across Vest-Spitsbergen to the Newton Mountain and across the Hinlopen Strait and further over the unknown island Nord-Ost-Landet (North East Land). Here they hoped to reach the pack ice of the North Pole and they wanted to fly parallel to the pack ice in western direction until the north western point of the island Vest-Spitsbergen, turn south to return to the Is Fjord passing “the steep, wild romantic west coast”, as Löwe wrote.

On the morning of Sunday, 8 July 1923 the reflection from the mountains could clearly be seen in the quiet waters of the Is Fjord. In the west they could see the Alkhorn with its three tops. The water was crystal clear.

On the morning of Sunday, 8 July 1923 the reflection from the mountains could clearly be seen in the quiet waters of the Is Fjord. In the west they could see the Alkhorn with its three tops. The water was crystal clear.

The pilot on this flight was Arthur Neumann, an experienced pilot. In 1919 he started to work for Deutsche Luft Reederei GmbH and moved in 1923 to Jfa. He was immediately sent to Spitsbergen on the “Junkers Spitzbergen Expedition”. Before departure from the camp, Neumann checked his Junkers Type Fw, D260 “Eisvogel”, while Löwe started to load the necessary equipment like food for three weeks, weapons, skis and different kind of tools. Also a camera and a Görz movie camera were brought along. The cabin of the Junkers Type Fw had been stripped for its chairs and a table was mounted. Löwe tightened his maps to this table and informed Arthur Neumann that he was ready for take-off.

At 1140am Arthur Neumann started the BMW-engine and taxied across the water of the Is Fjord. After a short run he took off and flew towards Advent Bay passing the houses of the mineworkers. Via Cape Heer they disappeared in the north eastern direction. In front of them the impressive 90km long Is Fjord and soon they are surrounded by steep mountains and flying above glaciers. No cloud visible, pure and clear air as far as one can see.

The engine gives up?

But soon their idyllic flight was interrupted by a hampering engine. As soon as more power was given; it started to make funny noises. Löwe suggested Arthur Neumann to return, but Arthur Neumann waved that he would continue. At 1240pm they left the Billen Bay. Löwe had corrected already some of the maps of the Norwegian Expedition of 1909-1910. He continuously made pictures, filmed while standing in the cockpit parts of the unbelievable outside scenery.

The black 150km long granite mountains of the Chydenius Mountains were nearly blocking their way. The Wijde Bay led the water to the north side of the Vest-Spitsbergen Island and into the Polar Sea. Because of the problems with the engine they only managed to fly at a height of 1,700m, while the Newton Mountain has a height of 1,730m. Strong winds play with the small seaplane and it gets harder for Löwe to film the scenery. Löwe gave instructions about the routing by tapping Arthur Neumann on the shoulder with a ski pool. As long as the ski pool rested on his left shoulder Arthur Neumann would turn to the left. After a while the course was changed and they now flew in north-north eastern direction. Instead of mountaintops, they now saw the massive glaciers, where one could easily land with a seaplane. The glacier rested on the north side of the area called Ny Friesland and came down along the east side and near the Hindelop Strait.

Turning west

After a long flight overland they finally reach water at 0200pm: the Lomme Bay. The colours were described as running from clear blue to deep green. After another 2,5 hours flight they reached a height of 2,000m. They could overlook more than 100 kilometres across the Nord-Ost-Landet, where the inland ice floated like a lava stream towards the Hindelop Strait. The strong headwinds slowed down the seaplane while it flew in northern direction. Any corrections of the course were met by strong winds and pushed the aircraft back in southern direction. The Wahlenberg Bay was frozen over, while the entrance of the Hindelop Strait was free of ice. The icecap of the Nord-Ost-Landet was now far away. They were now at 80° northern latitude and according to Löwe they could have easily continued to 81° or 82°. At Walvis Island they passed the 80° northern latitude and now they turned the seaplane in a western course towards Welcome Point.

At 0300pm they found themselves above the Gråhuken (Grey Hock), the most northern point of the Andreeland. On the port side they could clearly see the Wijde Fjord and the characteristic mountains surrounding Green Harbour. In the west they could also see the blue side of the pack ice of the North Pole. Löwe wrote: “…When looking at this scenery one forgets his worries at home!”

Meanwhile, measurements showed that the outside temperature at 2,200m was just 1 Degree Celsius, which was four degrees less than at the point of departure. The sea below was filled with icebergs. At that point they were well 1,110km from the North Pole and a seven to eight hours flight would have taken them there. But since they did not had the right equipment their changes of survival in case of a forced landing equalled zero.

At 0314pm the little seaplane crossed the Reinhalvøya (the “Reindeer” peninsula) and in the distance the Broad Bay (filled with floating ice) could be seen. They lowered the aircraft for a low pass. Löwe wanted to film the floating ice. While flying at 500m Arthur Neumann shouts: “Ice bear ahead!” But this soon turned out to be an iceberg. Löwe had misunderstood Arthur Neumann.

Finally at 0400pm they reached the Danskøya (Danish Islands) and pass Virgo Harbour at a height of 1,500m. They passed the two small cabins built by the unfortunate Swedish balloonists S A Andree, Nils Strindberg and Knut Frænkel, who perished with their balloon while attempting to fly to the North Pole back in 1897.

The last kilometres

Meanwhile, fog had arrived at the west coast of Spitsbergen and it had forced them to fly from Smerenburg Bay across the mountains of the Reusch Peninsula to the Magdalena Bay and further across the Liljenhök Glacier to the Cross Bay. This was followed by two nervous hours along the westside of Vest-Spitsbergen. They passed the steep mountains of the Island Prins Karl Forland and the Forland Sound. The Tre Kronor Mountain was circled before they headed for their final destination at the Is Fjord. Now they crossed the Kong Oskar II Land before they found themselves flying above the Is Fjord. At 0615pm Arthur Neumann put down the seaplane on the sea and taxied towards land. After a more than 6 hours lasting flight they had seen more scenery than they would ever see again. And their luck with the weather ran out just a few hours after their landing: from the west came a storm with rain and strong winds… The 1,000km long flight to the pack ice had come to an end.

Meanwhile, fog had arrived at the west coast of Spitsbergen and it had forced them to fly from Smerenburg Bay across the mountains of the Reusch Peninsula to the Magdalena Bay and further across the Liljenhök Glacier to the Cross Bay. This was followed by two nervous hours along the westside of Vest-Spitsbergen. They passed the steep mountains of the Island Prins Karl Forland and the Forland Sound. The Tre Kronor Mountain was circled before they headed for their final destination at the Is Fjord. Now they crossed the Kong Oskar II Land before they found themselves flying above the Is Fjord. At 0615pm Arthur Neumann put down the seaplane on the sea and taxied towards land. After a more than 6 hours lasting flight they had seen more scenery than they would ever see again. And their luck with the weather ran out just a few hours after their landing: from the west came a storm with rain and strong winds… The 1,000km long flight to the pack ice had come to an end.

Notes:

(1) Until July 1924 the official name of the Junkers F13 was Junkers Type F. Type Fw was the designation for the seaplane version of the Type F. The letter “w” stood for Wasser – Water.

(2) The “Ameland” was owned by the Dutch shipping-owner company Triton. It weighed 3,511 Tons. Built in 1916, in 1918 seized by US Authorities as military transport, 1919 returned to owners, 1927 sold to Westers, Rotterdam renamed “Slotlaan”.

(3) Pictures of the Junkers Spitsbergen Expedition can be found on the website of the National Library in Oslo: http://nabo.nb.no/trip?_b=AMUNDSEN&_i=101&_q=10&_l=WWW_L&emne=%27Ekspedisjoner%2C+Nordpolen+fart%F8yet+Maud%2C+Fly+Elisabeth%27 Press “Neste liste” for more pictures.